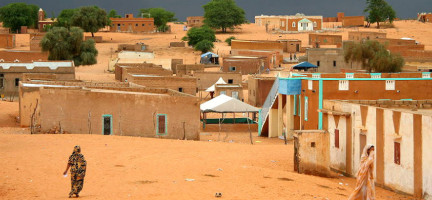

Mauritanie

Page en construction.

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Legal and institutional framework

The land sector in Mauritania is governed by a combination of different legal sources, including customary law and tribal rights, Islamic law and the legacy of the French Codes.

Article 15 of the Constitution of Mauritania guarantees the right to own property and the right of inheritance. However, the law can “limit the extent of the exercise of private property if the exigencies of economic and social development necessitate it”. There is a juridical regime for expropriation of land, but this can only take place “when public utility commands it and after a just and prior indemnity”. The allocation of Waghf land (religious endowments) and Waghf assets and foundations are also recognized and protected by law. Article 57 confirms that “transfers of property from the public sector to the private sector” is of the domain of the law [1].

The Land Code (Ordinance 83-127 of 5 June 1983) represents the most recent major land sector reform in Mauritania. According to Article 1, “the land belongs to the nation and all Mauritanians and without discrimination of any kind, some inhabitants own their own lands. By complying with the laws of ownership the land can thus be a private property". Article 2 of the Land Code confirms that “The State recognizes and guarantees private ownership of land which, in accordance with Sharia, contributes to the economic and social development of the owner, thus of the country”. Article 2 of the Land Code also ends Mauritania’s recognition of tribal property, stating that “any property right that is not tied directly to any person or entity and which does not result in a legally protected development is non-existent”. However, according to Article 6, “collective rights legitimately acquired under the previous regime, previously confined to farmland, benefiting all those who have either participated in the initial development or contributed to the sustainability of the operation” [2].

Despite this, most land in Mauritania is in practice governed by customary law, which almost fully based on Sharia law. Customary land tenure is most prevalent in rural areas, where traditional agreements are recognized as evidence of property rights [3].

In rangeland areas, the Pastoral Code of 2000 (Law No. 2000-44) recognizes usufruct rights of pastoralists, which are given priority over cultural uses of the land [3].

The revised Forest Code (Law No. 2007-055) lays out the framework for the creation, management and protection of forests, parks, reserves and protected areas, whether belonging to the State or individuals. State forests have specific protections, and there is scope for granting usufruct use of such lands. A separate law, No. 98-016, governs the sustainable participatory management of oases [3].

The Investment Code of 2012 (Law No. 2012-052) facilitates investments into Mauritania’s agricultural sector. This Code established the introduction and use of Investment Certificates as a tool for the simplification of agribusiness investment [3].

Land tenure

Many individual and collective land rights holders in Mauritania are not able to register their land as the registration process is considered quite complicated, resulting in high levels of land tenure insecurity in the country. Even the Land Code revisions of 1990 do not provide sufficient security for women or smallholders with usufructuary rights. Formal recognition of land rights of small farmers is only available through associations and cooperatives. Landlessness is also prevalent, though there have been attempts to address the phenomenon, including through a 1990 revision of the 1983 Land Code which recognizes some long-term land users as owners. In a limited number of cases of large-scale irrigation projects that have risked displacing local communities, land has been distributed to landless peasants as compensation, as in Kaédi and Boghé. Lack of access to land is a major factor contributing to poverty in the country; many former slaves continue working for their former enslavers due to lack of alternative land options [3].

The 1983 Land Code defines the country’s main land tenure regime. The reforms brought about through the Code reinforce the role of the State in land management and land allocation processes, and abolished traditional land tenure. All land, except plots owned privately by individuals, is designated State land. Privately owned land is defined as land registered by individuals or land that has been developed (or partially developed) as a result of a concession or of Law 60-139 of 1960 on the reorganization of the state. Between passage of the law in 1960 and the year 2000, more than 27,000 full freehold titles were issued, primarily in urban areas, along with 500,000 provisional title deeds in Nouakchott [3].

Customary tenure is the most common form of land governance in rural areas, though it is not recognized under the law. There are, however, formally recognized rights for pastoralists in rangeland areas. In areas where customary tenure prevails, large plots of community land are managed by traditional land chiefs who ensure that everyone in the community is granted access to the land. Such communities also often designate land for use by pastoralists, including for the conditions of movement and exploitation of natural resources, though the right of the land is always retained by the community. Roughly 5 per cent of land is governed by such usufruct transfer agreements [3].

The adoption of the land reform brought associated land rights, which were transferred through definitive grants (concessions) allocated by the State. The legal and administrative system still recognizes pre-existing rights, such us customary or tribal rights largely based on Sharia law – which in turn includes different forms of land tenure and sources of rights – and are recognized by traditional agreements. This, however, contradicts the principles of the 1983 reform, as the latter includes the intention to abolish traditional forms of land tenure. This confusion has fueled tensions and led to a rather unclear regularization of tribal rights in conflict-affected areas, such as the Senegal river region.

Between 1983 and 2010, decentralized and deconcentrated bodies, such as walis (governors) and hakims (prefects), had authority over rural areas. This changed with the adoption of a decree in 2010, which further entrenched centralized control and allocation of rural land, becoming the jurisdiction of national ministries.

There is no national-level cadastral plan or land register. An electronic land registry was established in Nouakchott in 2014, which eliminated duplicate and false titles, though the initiative was temporary. Land management in urban areas is the responsibility of the Ministry of Housing, Urban Development and Regional Management. Land registration activities are primarily concentrated in urban areas, while rural land users are not able to obtain official documentation and registration of their rights [3].

Land titles can be obtained through the Ministry of Finance, the Direction des Domaines (land department) and the Ministries of Urban Planning and Rural Development, including through their regional offices. However, the process for obtaining land titles is considered a long and complicated procedure due to the number of ministries and departments involved. Regional offices also lack resources [3].

Land value

In the early 2000s, Mauritania adopted a decentralization policy, shifting some of the fiscal responsibilities to municipal authorities. Communal fiscal commissions oversee the valuation of rental properties. Land taxes for both built-up and agricultural land, as well as housing taxes, are collected by municipal authorities. Built property is taxed, which must be paid by the property owner, and is calculated based on the rental value at a rate between 3 per cent and 10 per cent (in practice a rate of 8 per cent is applied) [12]. Joint Order No. R-558 of 2001 sets the amounts of fees and the final transfer price of concessions in rural areas.

Land use

Up until a series of droughts that occurred in the 1970s, land use in Mauritania was dominated by nomadism and pastoralism. Around 38 per cent of land is used for agricultural purposes, which includes pastoralism and fishing. However, desertification and urbanization trends are at risk of reducing the availability of agricultural land. The size of forested areas has been declining steadily since the 1990s, and more recently due to forest fires. Forested lands represent less 0.3 per cent of the country’s total area.

Rapid urban growth is changing how land is used and is increasing competition over arable and habitable land. The vast majority of Mauritania’s population lives on just one-fifth of the land, as most of the country is considered uninhabitable. The Senegal River Valley is considered the most fertile area of Mauritania. Changes in land use patterns are further impacted by disappearing traditional knowledge, the overexploitation of groundwater resources, land fragmentation and unsustainable practices, which also increase Mauritania’s vulnerability to climate change. Sand dunes from the east are also encroaching on urban centres. Since 2000, the Government of Mauritania has engaged in the Green Belt initiative for Nouakchott, which aims is to protect the capital city from further desertification [3] [6].

Land development

The Local Government Code of 2008 includes legal provisions for land development and planning that have been transferred to decentralized authorities and municipalities.

It is possible for both investors and individuals to acquire state-owned land. Agriculture is the major source of attraction for investors, and the National Agricultural Development Plan (PNDA) aims to intensify and diversify the country’s agricultural production by 2025. The Investment Code promotes land-related investment through incentives such as special benefits for medium-sized enterprises or favourable conditions in Free Zones.

There are three major agricultural investment projects in the Senegal River Valley currently operating, each of about 10,000 hectares in size. For permission to develop land for these project, investors first apply to the Ministry of Economy and Finance and then register the land that they have been granted to the Direction des Domaines (land department) under the Ministry of Housing. If the investor has purchased land, they must still register at the Direction des Domaines, however there are rules in place that allow foreign investors to circumvent this process by obtaining a Certificate of Investment. Many communities in areas governed by customary law, however, are against these investor-lead developments of State-granted land [3].

Large scale land development projects, such as in the municipality M’Bagne, are areas where traditional land users and practices confront modern laws and developers. In the M’Bagne area, a development site of nearly 20,000 hectares supervised by the Ministry of Environment, a parcel map showing existing land rights of farmers was drawn up as a way to avoid conflicts.

The National Agricultural Development Plan encourages the intensification and diversification of agricultural production, especially through agribusiness investments by medium-sized companies and multinationals. The Government of Mauritania has also encouraged Land development through large-scale land acquisitions and promoted Special Economic Zones.

Planning provisions also exist in forestry policy. This puts in place plans to manage and control land clearing, overgrazing, bush fires and firewood exploitation. The revised Forest Code concerns both state forests and those of local communities and individuals.

Land dispute resolution

Since the adoption of the 1983 land reform, conflicts around land and the access to natural resources have been on the rise in Mauritania. Land-related disputes are typically over Mauritania’s scarce fertile lands, usually in the form of conflict between pastoralists and farmers. Other sources of land disputes are large-scale mining projects, agribusiness investments in the Senegal River Valley and ethnic tensions [3].

The Senegal River Valley is one of the areas most affected by post-reform violence, where herders and farmers once lived together harmoniously, based on cyclic and complementary land use arrangements. Between 1989 and 1992, however, lack of clarity on the definition of land rights, their recognition, delimitation and materialization triggered an episode of violent conflict between farmers and herders regarding land use rights on the Mauritania-Senegal border. Black population groups were expelled as they were not considered Mauritanian and others in the Valley had their land expropriated. In 2007, the then President called for the return of 35,000 refugees, which involved the question of the restitution of their lost lands.

Conflicts have also occurred as the result of settlement programs aiming for a definitive sedentarization of the herder groups of the Peuls and the Haratine in areas officially inhabited by the Wolofs, Soninkés, Haalpularen and Moorish. Furthermore, government-promoted land development and investment policies have facilitated access to land titles for national agribusiness entities that dispose of considerable financial resources to exploit and develop land. These initiatives have encountered local resistance and protest.

Other land conflicts take place in urban areas, resulting from unclear land and property management and land information. They are further fueled by unplanned and informal occupations in certain peri-urban areas and the sometimes-questionable application of land law.

In 2000, land dispute resolution commissions were created at the wilaya and hakem levels. Their mission is to resolve conflicts by finding private arrangements and friendly solutions. If these instances fail to resolve a conflict, the national commission of collective land conflicts intervenes, which is informed and trained by the Ministry of Rural Development and Environment. National courts are rarely called upon, as for many, they are considered insufficiently effective and lacking objectivity. The absence of a national registry is a major roadblock for the mediation and settlement of land disputes, particularly in rural areas [3].

Women’s land rights

The Land Code guarantees equal land rights to women and men. However, in rural areas where customary practices are the norm, women still face difficulty in accessing and managing land. Only 8 per cent of title dees in Mauritania are held by women, primarily in cities where customary practices have less influence and women are more independent. In the Senegal River Valley, for example, only 5 per cent of title deeds are held by women, while Trarza has the highest levels of land ownership by women. Women are able to inherit land, but patriarchal practices encourage women to be given movable property rather than land as a way of ensuring land remains in the man’s family [3] [5].

Women often do not have full information on the procedure for acquiring land titles, despite their strong interest in obtaining titles to secure their access to land. They are also often illiterate, unknowledgeable about their rights or lacking the funds needed for the process of registration. Women, and especially women’s agricultural cooperatives, are encouraged by the government to register their land, but in practice there is no legislation that prevents discrimination against women. There are very few women in government land management or land conflict resolution positions [3] [5].

Key links and documents

[1] Constitution of Mauritania , 1991 (revised 2012).

[2] Mauritanian Network for Human Right in the USA. Land Rights.

[3] Hennings, M. (2021). Mauritania - Context and Land Governance. Land Portal.

[4] FAOSTAT (2021). Mauritania.

[5] The World Bank (2015). Women’s Access to Land in Mauritania: a case study in preparation for the COP.

[7] Choplin, A. and Ould Bah, M. F. (2018). Foncier, droit et propriété : au cœur de la société mauritanienne. In A. Choplin & M. Fall Ould Bah (Eds.), Foncier, droit et propriété en Mauritanie (pp. 15-23). Centre Jacques-Berque.

[8] Ould al Bara, Y. (2018). L’islam et la propriété foncière en Mauritanie. In A. Choplin & M. Fall Ould Bah (éds.), Foncier, droit et propriété en Mauritanie (pp. 25-67). Centre Jacques-Berque.

[9] The World Bank (2024). The World Bank in Mauritania.

[10] World Bank Group (2020). Doing Business 2020: Mauritania Economy Profile.

[11] Rochegude, A. and Plançon, C. (2009). Décentralisation, acteurs locaux et foncier: Fiches pays Mauritanie.

[12] PWC (2024). Mauritania: Individual – Other Taxes.

Clause de non-responsabilité

Les informations contenues dans cette page sont basées sur l'ensemble des connaissances développées par ONU-Habitat, GLTN et les partenaires de l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier. Les désignations utilisées et la présentation du matériel n'impliquent l'expression d'aucune opinion de la part du Secrétariat des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique de tout pays, territoire, ville ou zone, ou de ses autorités, ou concernant la délimitation. de ses frontières ou limites, ou concernant son système économique ou son degré de développement. Les informations peuvent contenir des inexactitudes en raison de la ou des sources de données et ne reflètent pas nécessairement les points de vue d'ONU-Habitat ou de ses organes directeurs.

La page de la Mauritanie est encore en construction. Partagez avec nous toute information, ressource ou correction pertinente pour enrichir notre bibliothèque. Contactez l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org !

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Le pays insulaire des Comores, ou Union des Comores, est situé dans l’océan Indien, à l’extrémité nord du canal du Mozambique, au large de la côte est de l’Afrique. Les Comores ont des frontières maritimes avec la Tanzanie, le Mozambique, Madagascar, les Seychelles et Mayotte (administrées par la France). [6] Ces îles volcaniques forment un archipel d'un peu plus de deux mille kilomètres carrés [5] avec une population de moins d'un million d'habitants, dont 30 pour cent vivent dans des centres urbains. La capitale et la plus grande ville est Moroni sur l'île de la Grande Comore, tandis que l'île d'Anjouan est la plus densément peuplée [10] .

Djibouti a une superficie de 23 200 km² et abrite un million d'habitants. Environ 78 pour cent de la population vit dans des zones urbaines, la majeure partie se trouvant dans la ville de Djibouti et dans d'autres zones urbaines et périurbaines voisines. Le quart restant de la population vit dans les zones rurales et se consacre principalement au mode de vie traditionnel des pasteurs transhumants. [1] Traditionnellement, les communautés Afar et Issa sont des éleveurs de chameaux, de chèvres et de moutons. Le peuple Afar, résidant principalement dans la région nord de Djibouti, fait partie d'un groupe ethnique Afar plus large que l'on trouve principalement en Éthiopie, tandis que le peuple Issa, concentré dans la partie sud de Djibouti, partage des liens ethniques avec la Somalie voisine. [1] Les luttes pour le partage du pouvoir entre les Issas et les Afars ont conduit à une guerre civile qui a ravagé

L'Égypte se trouve dans le nord-est de l'Afrique, avec la vallée et le delta du Nil au cœur du pays. L'Égypte était l'une des principales civilisations de l'ancien Moyen-Orient.

L'urbanisation est un moteur clé du développement en Égypte, 75 pour cent du PIB est généré dans les zones urbaines et 80 pour cent des emplois se trouvent dans les villes existantes (rapport de diagnostic NUP, non publié). L'urbanisation en Égypte est passée de 26 pour cent en 1937 à 38 pour cent en 1960 et 44 pour cent en 1986. Ce pourcentage est tombé à environ 42,2 pour cent en 2017, non pas parce que le taux d'urbanisation égyptien est en baisse, mais plutôt en raison du manque d'urbanisation. une définition claire et unifiée des zones urbaines et rurales. En 2021, 43 % de la population totale égyptienne vivait dans des zones urbaines et des villes.

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

L'Irak est l'un des pays les plus orientaux de la région arabe. Il est bordé au nord par la Turquie, à l’est par l’Iran, à l’ouest par la Syrie et la Jordanie et au sud par l’Arabie saoudite et le Koweït.

L’Irak a une histoire unique en tant que « puissant moteur de croissance économique et commerciale régionale, et phare mondial de la culture et de l’apprentissage » (Bilan commun de pays 2009). Au cours des dernières décennies, il a enduré deux guerres successives du Golfe, des sanctions économiques, une intervention militaire et des conflits internes. L'instabilité politique, la nature centralisée des mécanismes de gouvernance, une allocation déséquilibrée des ressources et un manque d'investissement dans les infrastructures, l'environnement et les services sociaux ont eu un impact sur la capacité du pays à développer son économie et à répondre aux besoins de la population (ONU).

Lisez la nouvelle évaluation du secteur foncier en Jordanie !

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

89 pour cent des 6 millions d'habitants vivent dans des centres urbains, principalement le long de la côte. 6 pour cent de sa superficie de 10 230 km sont bâtis, 32 pour cent sont agricoles et le reste est couvert d'herbe, d'arbustes, de rochers ou de forêt.

Traditionnellement considéré comme un pays à revenu intermédiaire, l'économie du Liban est en déclin en raison des effets combinés des conflits régionaux, de la pandémie de COVID-19 et de l'explosion du port de Beyrouth.

Le Liban accueille plus d’un million de réfugiés syriens dispersés dans les communautés urbaines et rurales, ce qui exerce une pression supplémentaire sur les communautés d’accueil déjà pauvres et accroît la demande de logements abordables et de services de base.

Le pays s'étend sur 1 759 540 km2 dont plus de 90 % de la superficie totale est désertique ou semi-désertique. Combiné à l’augmentation prévue de la population, cela entraînera un certain nombre de défis majeurs dans le pays, notamment la fourniture de logements adéquats, de nourriture, d’eau potable, d’opportunités d’emploi, de soins de santé, d’éducation et de transport.

Page en construction!

Partagez avec L’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier. les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Lisez la nouvelle évaluation du secteur foncier à Oman !

Partagez avec L’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

La division spatiale et administrative à l'intérieur de la Cisjordanie occupée, y compris Jérusalem-Est et entre la Cisjordanie et la bande de Gaza, est considérée comme le plus grand défi auquel sont confrontées les villes et communautés palestiniennes ( ONU-Habitat (2017) Profil de l'État de Palestine. ). Le secteur agricole palestinien joue un rôle clé pour la croissance économique du pays, ainsi que comme catalyseur du développement social et de la durabilité environnementale. Cependant, les restrictions imposées par Israël aux activités économiques et productives, notamment les restrictions à la circulation des personnes et des biens, et le manque d'accès à la terre, à l'eau et à d'autres ressources naturelles nuisent gravement à l'économie palestinienne et à son potentiel de croissance ( FAO (2019) Analyse contextuelle pour le cadre de programmation pays pour la Palestine 2018-2022. ).

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Un référentiel de publications, de documents de recherche, d'articles et de liens vers des événements pertinents organisés par les partenaires de l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier enrichit les connaissances partagées. Neuf documents récemment publiés sur la Somalie sont désormais prêts à être téléchargés !

Page en construction!

Partagez avec l’Initiative Arabe sur le Foncier les documents, publications et autres informations qui peuvent être présentés ici. Écrivez à unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Officiellement connue sous le nom de République arabe syrienne, la Syrie est habitée par plus de 18 millions d'habitants et borde la mer Méditerranée à l'ouest, la Turquie au nord, l'Irak à l'est et au sud-est, la Jordanie au sud et la Palestine et le Liban au sud-ouest. . La Syrie s'étend sur 185 180 kilomètres carrés.

La Tunisie fait partie de la région du Maghreb en Afrique du Nord, bordée par l'Algérie à l'ouest et au sud-ouest, la Libye au sud-est et la mer Méditerranée à l'est et au nord. Il contient l’extrémité orientale des montagnes de l’Atlas et la partie nord du désert du Sahara, la majeure partie de son territoire restant étant constituée de terres arables. La majeure partie du sud du pays est un désert de sable, où les oueds sont secs la majeure partie de l'année et où l'eau douce est rare. La Tunisie compte également plusieurs îles, l'île de Djerba dans le golfe de Gabès étant la plus grande île d'Afrique du Nord.

Le Yémen, officiellement la République du Yémen, est un pays d'Asie occidentale, situé dans le coin sud-ouest de la péninsule arabique. Il borde l'Arabie saoudite au nord, Oman au nord-est et partage des frontières maritimes avec l'Érythrée, Djibouti et la Somalie.