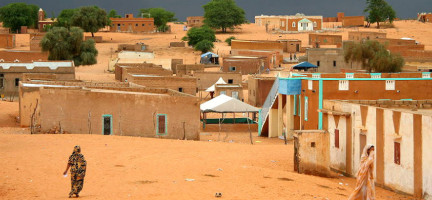

موريتانيا

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء.

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

Legal and institutional framework

The land sector in Mauritania is governed by a combination of different legal sources, including customary law and tribal rights, Islamic law and the legacy of the French Codes.

Article 15 of the Constitution of Mauritania guarantees the right to own property and the right of inheritance. However, the law can “limit the extent of the exercise of private property if the exigencies of economic and social development necessitate it”. There is a juridical regime for expropriation of land, but this can only take place “when public utility commands it and after a just and prior indemnity”. The allocation of Waghf land (religious endowments) and Waghf assets and foundations are also recognized and protected by law. Article 57 confirms that “transfers of property from the public sector to the private sector” is of the domain of the law [1].

The Land Code (Ordinance 83-127 of 5 June 1983) represents the most recent major land sector reform in Mauritania. According to Article 1, “the land belongs to the nation and all Mauritanians and without discrimination of any kind, some inhabitants own their own lands. By complying with the laws of ownership the land can thus be a private property". Article 2 of the Land Code confirms that “The State recognizes and guarantees private ownership of land which, in accordance with Sharia, contributes to the economic and social development of the owner, thus of the country”. Article 2 of the Land Code also ends Mauritania’s recognition of tribal property, stating that “any property right that is not tied directly to any person or entity and which does not result in a legally protected development is non-existent”. However, according to Article 6, “collective rights legitimately acquired under the previous regime, previously confined to farmland, benefiting all those who have either participated in the initial development or contributed to the sustainability of the operation” [2].

Despite this, most land in Mauritania is in practice governed by customary law, which almost fully based on Sharia law. Customary land tenure is most prevalent in rural areas, where traditional agreements are recognized as evidence of property rights [3].

In rangeland areas, the Pastoral Code of 2000 (Law No. 2000-44) recognizes usufruct rights of pastoralists, which are given priority over cultural uses of the land [3].

The revised Forest Code (Law No. 2007-055) lays out the framework for the creation, management and protection of forests, parks, reserves and protected areas, whether belonging to the State or individuals. State forests have specific protections, and there is scope for granting usufruct use of such lands. A separate law, No. 98-016, governs the sustainable participatory management of oases [3].

The Investment Code of 2012 (Law No. 2012-052) facilitates investments into Mauritania’s agricultural sector. This Code established the introduction and use of Investment Certificates as a tool for the simplification of agribusiness investment [3].

Land tenure

Many individual and collective land rights holders in Mauritania are not able to register their land as the registration process is considered quite complicated, resulting in high levels of land tenure insecurity in the country. Even the Land Code revisions of 1990 do not provide sufficient security for women or smallholders with usufructuary rights. Formal recognition of land rights of small farmers is only available through associations and cooperatives. Landlessness is also prevalent, though there have been attempts to address the phenomenon, including through a 1990 revision of the 1983 Land Code which recognizes some long-term land users as owners. In a limited number of cases of large-scale irrigation projects that have risked displacing local communities, land has been distributed to landless peasants as compensation, as in Kaédi and Boghé. Lack of access to land is a major factor contributing to poverty in the country; many former slaves continue working for their former enslavers due to lack of alternative land options [3].

The 1983 Land Code defines the country’s main land tenure regime. The reforms brought about through the Code reinforce the role of the State in land management and land allocation processes, and abolished traditional land tenure. All land, except plots owned privately by individuals, is designated State land. Privately owned land is defined as land registered by individuals or land that has been developed (or partially developed) as a result of a concession or of Law 60-139 of 1960 on the reorganization of the state. Between passage of the law in 1960 and the year 2000, more than 27,000 full freehold titles were issued, primarily in urban areas, along with 500,000 provisional title deeds in Nouakchott [3].

Customary tenure is the most common form of land governance in rural areas, though it is not recognized under the law. There are, however, formally recognized rights for pastoralists in rangeland areas. In areas where customary tenure prevails, large plots of community land are managed by traditional land chiefs who ensure that everyone in the community is granted access to the land. Such communities also often designate land for use by pastoralists, including for the conditions of movement and exploitation of natural resources, though the right of the land is always retained by the community. Roughly 5 per cent of land is governed by such usufruct transfer agreements [3].

The adoption of the land reform brought associated land rights, which were transferred through definitive grants (concessions) allocated by the State. The legal and administrative system still recognizes pre-existing rights, such us customary or tribal rights largely based on Sharia law – which in turn includes different forms of land tenure and sources of rights – and are recognized by traditional agreements. This, however, contradicts the principles of the 1983 reform, as the latter includes the intention to abolish traditional forms of land tenure. This confusion has fueled tensions and led to a rather unclear regularization of tribal rights in conflict-affected areas, such as the Senegal river region.

Between 1983 and 2010, decentralized and deconcentrated bodies, such as walis (governors) and hakims (prefects), had authority over rural areas. This changed with the adoption of a decree in 2010, which further entrenched centralized control and allocation of rural land, becoming the jurisdiction of national ministries.

There is no national-level cadastral plan or land register. An electronic land registry was established in Nouakchott in 2014, which eliminated duplicate and false titles, though the initiative was temporary. Land management in urban areas is the responsibility of the Ministry of Housing, Urban Development and Regional Management. Land registration activities are primarily concentrated in urban areas, while rural land users are not able to obtain official documentation and registration of their rights [3].

Land titles can be obtained through the Ministry of Finance, the Direction des Domaines (land department) and the Ministries of Urban Planning and Rural Development, including through their regional offices. However, the process for obtaining land titles is considered a long and complicated procedure due to the number of ministries and departments involved. Regional offices also lack resources [3].

Land value

In the early 2000s, Mauritania adopted a decentralization policy, shifting some of the fiscal responsibilities to municipal authorities. Communal fiscal commissions oversee the valuation of rental properties. Land taxes for both built-up and agricultural land, as well as housing taxes, are collected by municipal authorities. Built property is taxed, which must be paid by the property owner, and is calculated based on the rental value at a rate between 3 per cent and 10 per cent (in practice a rate of 8 per cent is applied) [12]. Joint Order No. R-558 of 2001 sets the amounts of fees and the final transfer price of concessions in rural areas.

Land use

Up until a series of droughts that occurred in the 1970s, land use in Mauritania was dominated by nomadism and pastoralism. Around 38 per cent of land is used for agricultural purposes, which includes pastoralism and fishing. However, desertification and urbanization trends are at risk of reducing the availability of agricultural land. The size of forested areas has been declining steadily since the 1990s, and more recently due to forest fires. Forested lands represent less 0.3 per cent of the country’s total area.

Rapid urban growth is changing how land is used and is increasing competition over arable and habitable land. The vast majority of Mauritania’s population lives on just one-fifth of the land, as most of the country is considered uninhabitable. The Senegal River Valley is considered the most fertile area of Mauritania. Changes in land use patterns are further impacted by disappearing traditional knowledge, the overexploitation of groundwater resources, land fragmentation and unsustainable practices, which also increase Mauritania’s vulnerability to climate change. Sand dunes from the east are also encroaching on urban centres. Since 2000, the Government of Mauritania has engaged in the Green Belt initiative for Nouakchott, which aims is to protect the capital city from further desertification [3] [6].

Land development

The Local Government Code of 2008 includes legal provisions for land development and planning that have been transferred to decentralized authorities and municipalities.

It is possible for both investors and individuals to acquire state-owned land. Agriculture is the major source of attraction for investors, and the National Agricultural Development Plan (PNDA) aims to intensify and diversify the country’s agricultural production by 2025. The Investment Code promotes land-related investment through incentives such as special benefits for medium-sized enterprises or favourable conditions in Free Zones.

There are three major agricultural investment projects in the Senegal River Valley currently operating, each of about 10,000 hectares in size. For permission to develop land for these project, investors first apply to the Ministry of Economy and Finance and then register the land that they have been granted to the Direction des Domaines (land department) under the Ministry of Housing. If the investor has purchased land, they must still register at the Direction des Domaines, however there are rules in place that allow foreign investors to circumvent this process by obtaining a Certificate of Investment. Many communities in areas governed by customary law, however, are against these investor-lead developments of State-granted land [3].

Large scale land development projects, such as in the municipality M’Bagne, are areas where traditional land users and practices confront modern laws and developers. In the M’Bagne area, a development site of nearly 20,000 hectares supervised by the Ministry of Environment, a parcel map showing existing land rights of farmers was drawn up as a way to avoid conflicts.

The National Agricultural Development Plan encourages the intensification and diversification of agricultural production, especially through agribusiness investments by medium-sized companies and multinationals. The Government of Mauritania has also encouraged Land development through large-scale land acquisitions and promoted Special Economic Zones.

Planning provisions also exist in forestry policy. This puts in place plans to manage and control land clearing, overgrazing, bush fires and firewood exploitation. The revised Forest Code concerns both state forests and those of local communities and individuals.

Land dispute resolution

Since the adoption of the 1983 land reform, conflicts around land and the access to natural resources have been on the rise in Mauritania. Land-related disputes are typically over Mauritania’s scarce fertile lands, usually in the form of conflict between pastoralists and farmers. Other sources of land disputes are large-scale mining projects, agribusiness investments in the Senegal River Valley and ethnic tensions [3].

The Senegal River Valley is one of the areas most affected by post-reform violence, where herders and farmers once lived together harmoniously, based on cyclic and complementary land use arrangements. Between 1989 and 1992, however, lack of clarity on the definition of land rights, their recognition, delimitation and materialization triggered an episode of violent conflict between farmers and herders regarding land use rights on the Mauritania-Senegal border. Black population groups were expelled as they were not considered Mauritanian and others in the Valley had their land expropriated. In 2007, the then President called for the return of 35,000 refugees, which involved the question of the restitution of their lost lands.

Conflicts have also occurred as the result of settlement programs aiming for a definitive sedentarization of the herder groups of the Peuls and the Haratine in areas officially inhabited by the Wolofs, Soninkés, Haalpularen and Moorish. Furthermore, government-promoted land development and investment policies have facilitated access to land titles for national agribusiness entities that dispose of considerable financial resources to exploit and develop land. These initiatives have encountered local resistance and protest.

Other land conflicts take place in urban areas, resulting from unclear land and property management and land information. They are further fueled by unplanned and informal occupations in certain peri-urban areas and the sometimes-questionable application of land law.

In 2000, land dispute resolution commissions were created at the wilaya and hakem levels. Their mission is to resolve conflicts by finding private arrangements and friendly solutions. If these instances fail to resolve a conflict, the national commission of collective land conflicts intervenes, which is informed and trained by the Ministry of Rural Development and Environment. National courts are rarely called upon, as for many, they are considered insufficiently effective and lacking objectivity. The absence of a national registry is a major roadblock for the mediation and settlement of land disputes, particularly in rural areas [3].

Women’s land rights

The Land Code guarantees equal land rights to women and men. However, in rural areas where customary practices are the norm, women still face difficulty in accessing and managing land. Only 8 per cent of title dees in Mauritania are held by women, primarily in cities where customary practices have less influence and women are more independent. In the Senegal River Valley, for example, only 5 per cent of title deeds are held by women, while Trarza has the highest levels of land ownership by women. Women are able to inherit land, but patriarchal practices encourage women to be given movable property rather than land as a way of ensuring land remains in the man’s family [3] [5].

Women often do not have full information on the procedure for acquiring land titles, despite their strong interest in obtaining titles to secure their access to land. They are also often illiterate, unknowledgeable about their rights or lacking the funds needed for the process of registration. Women, and especially women’s agricultural cooperatives, are encouraged by the government to register their land, but in practice there is no legislation that prevents discrimination against women. There are very few women in government land management or land conflict resolution positions [3] [5].

Key links and documents

[1] Constitution of Mauritania , 1991 (revised 2012).

[2] Mauritanian Network for Human Right in the USA. Land Rights.

[3] Hennings, M. (2021). Mauritania - Context and Land Governance. Land Portal.

[4] FAOSTAT (2021). Mauritania.

[5] The World Bank (2015). Women’s Access to Land in Mauritania: a case study in preparation for the COP.

[7] Choplin, A. and Ould Bah, M. F. (2018). Foncier, droit et propriété : au cœur de la société mauritanienne. In A. Choplin & M. Fall Ould Bah (Eds.), Foncier, droit et propriété en Mauritanie (pp. 15-23). Centre Jacques-Berque.

[8] Ould al Bara, Y. (2018). L’islam et la propriété foncière en Mauritanie. In A. Choplin & M. Fall Ould Bah (éds.), Foncier, droit et propriété en Mauritanie (pp. 25-67). Centre Jacques-Berque.

[9] The World Bank (2024). The World Bank in Mauritania.

[10] World Bank Group (2020). Doing Business 2020: Mauritania Economy Profile.

[11] Rochegude, A. and Plançon, C. (2009). Décentralisation, acteurs locaux et foncier: Fiches pays Mauritanie.

[12] PWC (2024). Mauritania: Individual – Other Taxes.

تنصل

تعتمد المعلومات الواردة في هذه الصفحة على مجموعة المعرفة التي طورها برنامج الأمم المتحدة للمستوطنات البشرية وGLTN وشركاء مبادرة الأراضي العربية. التسميات المستخدمة وطريقة عرض المواد لا تعني التعبير عن أي رأي مهما كان من جانب الأمانة العامة للأمم المتحدة فيما يتعلق بالوضع القانوني لأي بلد أو إقليم أو مدينة أو منطقة، أو سلطاتها، أو فيما يتعلق بتعيين الحدود حدودها أو حدودها، أو فيما يتعلق بنظامها الاقتصادي أو درجة تطورها. قد تحتوي المعلومات على معلومات غير دقيقة بسبب مصدر (مصادر) البيانات ولا تعكس بالضرورة آراء موئل الأمم المتحدة أو هيئاته الإدارية.

صفحة موريتانيا لا تزال قيد الإنشاء. شارك معنا بأي معلومات أو موارد أو تصحيحات ذات صلة لإثراء مكتبتنا. اتصل بمبادرة الأراضي العربية على unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org !

اقرأ التقييم الجديد لقطاع الأراضي في الأردن!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

إن مستودع المنشورات والأوراق البحثية والمقالات والروابط للأحداث ذات الصلة من قبل شركاء مبادرة الأراضي العربية يثري المعرفة المشتركة. تسع وثائق تم إصدارها حديثًا حول الصومال جاهزة الآن للتنزيل!

العراق هو أحد بلدان أقصى شرق المنطقة العربية. يحدها من الشمال تركيا، ومن الشرق إيران، ومن الغرب سوريا والأردن، ومن الجنوب المملكة العربية السعودية والكويت.

يتمتع العراق بتاريخ فريد باعتباره "محركًا قويًا للنمو الاقتصادي الإقليمي والتجارة، ومنارة عالمية للثقافة والتعلم" (التقييم القطري المشترك 2009). وفي العقود الأخيرة، عانت من حربين خليجيتين متتاليتين، وعقوبات اقتصادية، وتدخل عسكري، وصراعات داخلية. وقد أثر عدم الاستقرار السياسي، والطبيعة المركزية لآليات الحكم، وعدم التوازن في تخصيص الموارد، ونقص الاستثمار في البنية التحتية والبيئة والخدمات الاجتماعية على قدرة البلاد على تطوير اقتصادها ودعم احتياجات السكان (الأمم المتحدة).

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

اليمن، رسميا الجمهورية اليمنية، هي دولة تقع في غرب آسيا، وتقع في الركن الجنوبي الغربي من شبه الجزيرة العربية. يحدها المملكة العربية السعودية من الشمال، وعمان من الشمال الشرقي، وتشترك في الحدود البحرية مع إريتريا وجيبوتي والصومال.

تونس جزء من منطقة المغرب العربي في شمال أفريقيا، تحدها الجزائر من الغرب والجنوب الغربي، وليبيا من الجنوب الشرقي، والبحر الأبيض المتوسط من الشرق والشمال. تحتوي على الطرف الشرقي لجبال الأطلس والأطراف الشمالية للصحراء الكبرى، مع كون معظم أراضيها المتبقية أراضٍ صالحة للزراعة. معظم الجزء الجنوبي من البلاد عبارة عن صحراء رملية، حيث تكون الوديان جافة معظم أيام السنة والمياه العذبة نادرة. يوجد في تونس أيضًا عدة جزر، جزيرة جربة في خليج قابس هي أكبر جزيرة في شمال إفريقيا.

تقع دولة جزر القمر، أو اتحاد جزر القمر، في المحيط الهندي عند الطرف الشمالي لقناة موزمبيق، قبالة الساحل الشرقي لأفريقيا. ولجزر القمر حدود بحرية مع تنزانيا وموزمبيق ومدغشقر وسيشيل ومايوت (التي تديرها فرنسا). [6] تشكل هذه الجزر البركانية أرخبيلًا مساحته تزيد قليلاً عن ألفي كيلومتر مربع [5] ويبلغ عدد سكانه أقل من مليون نسمة، يعيش 30 بالمائة منهم في المراكز الحضرية. عاصمتها وأكبر مدنها هي موروني في جزيرة القمر الكبرى، في حين أن جزيرة أنجوان هي الأكثر كثافة سكانية [10] .

تبلغ مساحة جيبوتي 23.200 كيلومتر مربع، ويسكنها مليون نسمة. يعيش حوالي 78% من السكان في المناطق الحضرية، مع التركيز الرئيسي في مدينة جيبوتي وغيرها من المناطق الحضرية وشبه الحضرية القريبة. يعيش الربع المتبقي من السكان في المناطق الريفية ويخصص معظمهم لأسلوب الحياة الرعوي التقليدي. [1] تقليديًا، تتكون مجتمعات عفر وعيسى من رعاة الإبل والماعز والأغنام. يعد شعب عفار، الذي يقيم أساسًا في المنطقة الشمالية من جيبوتي، جزءًا من مجموعة عرقية أكبر تتواجد في الغالب في إثيوبيا، في حين أن شعب عيسى، المتمركز في الجزء الجنوبي من جيبوتي، يتقاسم الروابط العرقية مع الصومال المجاورة. [1] أدت الصراعات على تقاسم السلطة بين قبيلتي عيسى وعفار إلى حرب أهلية دمرتها

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

اقرأ التقييم الجديد لقطاع الأراضي في سلطنة عمان!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org

تُعرف سوريا رسميًا باسم الجمهورية العربية السورية، ويسكنها أكثر من 18 مليون نسمة، ويحدها البحر الأبيض المتوسط من الغرب، وتركيا من الشمال، والعراق من الشرق والجنوب الشرقي، والأردن من الجنوب، وفلسطين ولبنان من الجنوب الغربي. . مساحة سوريا 185,180 كيلومتر مربع.

يعتبر التقسيم المكاني والإداري داخل الضفة الغربية المحتلة بما فيها القدس الشرقية وبين الضفة الغربية وقطاع غزة التحدي الأكبر الذي يواجه المدن والمجتمعات الفلسطينية ( موئل الأمم المتحدة (2017) ملف دولة فلسطين. ). يلعب القطاع الزراعي الفلسطيني دوراً رئيسياً في النمو الاقتصادي للبلاد، فضلاً عن كونه أداة تمكينية للتنمية الاجتماعية والاستدامة البيئية. ومع ذلك، فإن القيود التي تفرضها إسرائيل على الأنشطة الاقتصادية والإنتاجية، بما في ذلك القيود المفروضة على حركة الأشخاص والبضائع، وعدم إمكانية الوصول إلى الأراضي والمياه والموارد الطبيعية الأخرى، تضعف بشدة الاقتصاد الفلسطيني وإمكاناته للنمو ( منظمة الأغذية والزراعة (2019) تحليل السياق لـ إطار البرمجة القطرية لفلسطين 2018-2022. ).

ويعيش 89% من السكان البالغ عددهم 6 ملايين نسمة في المراكز الحضرية، ومعظمهم على طول الساحل. 6 في المائة من سطحها البالغ طوله 10230 كيلومتراً مبني، و32 في المائة زراعية، والأجزاء المتبقية مغطاة بالعشب والشجيرات والصخور والغابات.

يعتبر لبنان تقليديًا دولة متوسطة الدخل، وقد شهد الاقتصاد اللبناني تراجعًا بسبب الآثار المجمعة للصراعات الإقليمية ووباء كوفيد-19 وانفجار مرفأ بيروت.

يستضيف لبنان أكثر من مليون لاجئ سوري منتشرين في المجتمعات الحضرية والريفية، مما يزيد من الضغط على المجتمعات المضيفة الفقيرة بالفعل ويزيد من الطلب على السكن والخدمات الأساسية بأسعار معقولة.

وتمتد الدولة على مساحة 1,759,540 كيلومتر مربع، حيث أكثر من 90% من إجمالي مساحة الأرض صحراوية أو شبه صحراوية. وإلى جانب الزيادة المتوقعة في عدد السكان، سيؤدي ذلك إلى عدد من التحديات الرئيسية في البلاد بما في ذلك توفير السكن الملائم والغذاء ومياه الشرب النظيفة وفرص العمل والرعاية الصحية والتعليم والنقل.

تقع مصر في الركن الشمالي الشرقي من أفريقيا، مع وادي نهر النيل والدلتا في قلب البلاد، وكانت مصر واحدة من الحضارات الرئيسية في الشرق الأوسط القديم.

يعد التوسع الحضري محركًا رئيسيًا للتنمية في مصر، حيث يتم توليد 75 في المائة من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي في المناطق الحضرية و80 في المائة من الوظائف في المدن القائمة (تقرير تشخيصي لحزب الوحدة الوطنية، غير منشور). ارتفع معدل التحضر في مصر من 26 في المائة عام 1937 إلى 38 في المائة عام 1960 و44 في المائة عام 1986. وانخفضت هذه النسبة إلى نحو 42.2 في المائة عام 2017، ليس بسبب انخفاض معدل التحضر المصري، بل بسبب عدم وجود تعريف واضح وموحد للمناطق الحضرية والريفية. وفي عام 2021، كان 43 في المائة من إجمالي سكان مصر يعيشون في المناطق الحضرية والمدن.

الصفحة قيد الإنشاء!

شارك مع مبادرة الأراضي العربية وثائق ,منشورات وغيرها من المعلومات التي يمكن عرضها هنا. اكتب إلى unhabitat-arablandinitiative@un.org